善良無需考證

巴西著名導演沃爾特·塞勒斯正在籌備自己的新電影,一天,正為此一籌莫展的沃爾特到城市西郊辦事,在火車站前的廣場上遇到了一個十多歲的擦鞋小男孩。小男孩問道:「先生,您需要擦鞋嗎?」沃爾特低頭看了看自己腳上剛剛擦過不久的皮鞋,搖搖頭拒絕了。

就在沃爾特轉身走出十幾步之際,忽然見到那個小男孩紅著臉追上來,眼中滿是祈求:「先生,我整整一天都沒吃東西了,您能借給我幾個錢嗎?我從明天開始就多多努力擦鞋,保證一周後把錢還給您!」

沃爾特看著面前這個衣衫襤褸、面黃肌瘦的小男孩,不由的動了惻隱之心,就掏出幾枚硬幣遞到小男孩手裡。小男孩感激的道了一聲「謝謝」後,一溜煙就跑得沒影了。沃爾特搖了搖頭,因為這樣的街頭小騙子他已經見得太多了。

半個月後,忙著籌備新電影的沃爾特早已將借錢給小男孩的事忘得一乾二淨了。不料,就在他又一次經過西郊火車站時,突然看到一個瘦小的身影離的老遠就向他招手喊道:「先生,請等一等!」等到對方滿頭大汗的跑過來把幾枚硬幣交給他時,沃爾特才認出這是上次向他借錢的那個擦鞋小男孩。小男孩氣喘吁吁的說:「先生,我在這裡等您很久了,今天總算把錢還給您了!」沃爾特握著自己手裡被汗水濡濕的硬幣,心頭陡然升起一股暖流。

沃爾特不由地仔細端詳起面前的小男孩,突然,他發現這個小男孩其實很符合自己腦海中構想的主人公形象。於是,沃爾特把幾枚硬幣塞到小男孩衣兜里:「這點零錢是我誠心誠意給你的,就不用還了。」沃爾特對他神秘的一笑,又說道,「明天你到市中心的影業公司導演辦公室來找我,我會給你一個大大的驚喜。」

第二天一大早,門衛就告訴沃爾特,說外面來了一大群孩子。他詫異的出去一看,就見那個小男孩興奮的跑過來,一臉天真的說:「先生,這些孩子都是同我一樣沒有父母的流浪兒,聽說你有驚喜給我,我就把他們都帶來了,因為,我知道他們也渴望有驚喜!」

沃爾特真沒想到這樣一個窮困流浪的孩子竟會有一顆如此善良的心!既然人都帶來了,沃爾特就讓工作人員對這些孩子進行了觀察和篩選,最後,工作人員在這些孩子中,找出了幾個比小男孩更機靈,更適合出演劇本中的小主人公的人選。

但最終,沃爾特還是選擇只把小男孩留下來。他在錄用合同的免試原因一欄中只寫了這樣幾個字:你的善良,無需考核!

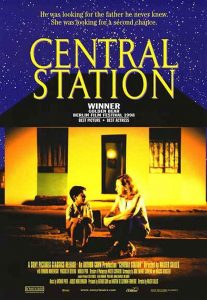

因為他覺得:在自己面臨困境的時候,卻依然能把本屬於自己一個人的希望,無私的分享給別人的人,最值得擁有人生的驚喜!而這個小男孩就是後來巴西家喻戶曉的明星文尼西斯·狄·奧利維拉。 在沃爾特的執導下,文尼西斯在劇中成功地扮演了小男孩主人公的角色,而電影《中央車站》也大獲好評,並獲得了1999年的奧斯卡金像獎。

若干年後,已成為一家影視文化公司董事長的文尼西斯寫了一本自傳,叫《我的演藝生涯》。

在書的扉頁上面,是沃爾特的親筆題字:你的善良,無需考核。下面還有一行小字,則是他對文尼西斯的評價:「是善良,曾經讓他把機遇讓給別的孩子;同樣也是善良,讓人生的機遇不曾錯過他!」。

「欣賞一個人,始於顏值,敬於才華,合於性格,久於善良,終於人 品。

人生就是這樣,和漂亮的人在一起,會越來越美;和陽光的人在一起,心裡就不會晦暗;和快樂的人在一起,嘴角就常帶微笑;和聰明的人在一起,做事就機敏;和大方的人在一起, 處事就不小氣;和睿智的人在一起,遇事就不迷茫。

借人之智,修善自己;學最好的別人,做最好的自己!」

(English story from Washington Post, different from Chinese one, good for reading )

ONE morning in late 1996, the Brazilian director Walter Salles was waiting for a flight in Rio de Janeiro when he was approached by a 9-year-old shoeshine boy. At the time, Mr. Salles was preparing to shoot his third feature film, ''Central Station,'' the tale of an older woman and a boy who meet at Rio's train station and then strike out on a journey into the hinterlands to find the boy's father.

Fernanda Montenegro, Brazil's doyenne of stage and film, had agreed to play the woman, Dora, but Mr. Salles had still not found anyone to play Josue, the child. ''In one full year we had tested 1,500 boys,'' he said. ''I was getting desperate.''

The shoeshine boy, Vinicius de Oliveira, had other concerns, however. ''It was raining that day, and I wasn't making any money,'' he recalled, speaking through an interpreter at the Toronto Film Festival. ''I couldn't shine Walter's shoes because he was wearing sneakers, but I asked if he could lend me some money so I could eat and I would pay him back. He told me, 'I'll give you the money to buy a sandwich, but you also have to do a screen test for me.' ''

When Vinicius finally showed up for the test, he brought his friends with him, ''the entire fraternity of shoeshine boys from the airport,'' Mr. Salles said, laughing. He chose Vinicius for the role because, he said, ''I was looking for a boy who knew what the battle for survival was, but who had not lost his innocence in doing so.

''I cannot even say that I found Vinicius. It's more honest to say that he found me.''

The story of how ''Central Station'' was made, over a vast territory, with a small budget and crew and many novice collaborators, embodies the theme of the film itself: the triumph of steadfastness over adversity. Both a portrait of present day Brazil and a two-person drama, ''Central Station,'' which opened on Friday, manages to be intimate and epic, local and universal.

''One day I woke up with this idea of a film about a quest,'' said Mr. Salles, 42. ''It was the search for a father that a kid had never met, the search of an old woman for the feelings that she had lost and the search somehow for a certain country that was not the country I was living in anymore.''

Mr. Salles's work is informed by the search for identity, both on a personal and national level, a concern stemming largely from his own background. Born in Brazil to a banking family, he spent part of his childhood in France and the United States where his father was a diplomat. When he returned to Brazil, he eventually decided to become a documentary filmmaker.

This combination of an outsider's perspective and an insider's understanding has shaped Mr. Salles's work. ''I think the fact that I have been raised in several different countries has given me both a sense of continuous exile and a desire to understand my own culture,'' he said recently in New York, speaking in fluent English.

The dark-haired Mr. Salles, who has kind eyes and a ready laugh, is both warm and disarmingly modest. ''When you come from a privileged part of Brazilian society, as I do, you have to opt either to be part of that culture of indifference or to understand what the country really is,'' he said.

His movie comes at a time when Brazilian cinema is once again flourishing. After a period of forced inactivity in the early 1990's, when the Government of President Fernando Collor de Mello froze individual bank accounts and shut down the state film agency, film production has risen to approximately 40 films a year.

But the reality of everyday life that ''Central Station'' depicts is harsh. In the film, Dora is a bitter woman who makes her living in Rio's Central Station, writing letters for illiterate people. She takes their money but discards the letters. One day she writes a letter for a mother and her little boy (Vinicius de Oliveira). When the mother is killed in an accident outside the station, Dora tries to sell the boy for adoption. Realizing that she has instead sold him to a sinister organization in which he may come to harm, she rescues the boy and the two set out on a bus trip to find his father.

For Mr. Salles, Dora is the epitome of modern Brazil, with its ''culture of cynicism.'' But as Dora grudgingly develops a bond with the boy ''she begins to understand that the boy's route and the boy's ordeal are comparable to her own,'' he said.

The growing friendship between these two -- more comradely than mother-son -- is, for Mr. Salles, a symbol of a Brazil where solidarity and compassion may be buried but are still present. His film is not utopian, but it celebrates the diversity both of the land and of what Mr. Salles calls the ''human geography'' that Dora and Josue encounter on their journey.

When the screenplay of ''Central Station,'' based on an idea of Mr. Salles's and written by Joao Emanuel Carneiro and Marcos Bernstein, won a prize sponsored by the Sundance Institute and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation in early 1996, it attracted the attention of Arthur Cohn, the Swiss independent producer who has won five Academy Awards (one for Vittorio De Sica's ''Garden of the Finzi-Continis'').

LIKE De Sica, Walter's approach is humanistic,'' said Mr. Cohn. ''De Sica taught me that there were four main points to making significant films. One was to cast actors who are right for the part, not just those with big names. Two was to shoot the film on authentic locations. Three was that sex, violence or special effects are not necessary unless they're intrinsic to the story.'' He smiled. ''Four was not to listen to everybody's advice, but to follow your intuition.''

With Mr. Cohn as producer, and with his principal cast finally in place Mr. Salles started the collaborative rehearsal process he had favored with his second film, ''Foreign Land'' (1995). ''It's a work almost like that of theater,'' said Ms. Montenegro, 69, in New York. ''For two months we sat around a table, reading and discussing the script.''

The long preparation allowed Mr. Salles to move quickly and to improvise once filming began in November 1996. During the filming of Ms. Montenegro's scenes in the railroad station, several passersby took her to be an actual letter-writer and asked her to write letters for them, scenes that made it into the movie. In following the journey of Dora and Josue, Mr. Salles had to move his team from Rio to remote regions of northeast Brazil, to the states of Bahia and Pernambuco. ''The transport from one place to another sometimes took three days on dirt roads,'' said Mr. Salles. ''It was like being in a circus for several weeks.''

Nor were conditions easy, due to the extreme heat and the poverty of the villages where Mr. Salles was filming. Yet the welcome that his crew received allowed the unforeseen to occur, as in a scene where Dora and Josue come upon a religious pilgrimage in full swing. Mr. Salles had the actual pilgrims recreate this candlelight vigil.

Mr. Salles is a largely self-taught filmmaker. After studying history and economics in college in Brazil, he attended only one year of film school, at the University of Southern California, before returning to Rio in 1981 to make documentaries.

His move toward feature films was gradual. In 1989, he directed ''Exposure,'' starring Peter Coyote and based on the Brazilian writer Rubem Fonseca's novel ''High Art.'' ''Foreign Land,'' about two young Brazilians bereft in Lisbon, delved into the themes of physical and spiritual voyage and of loss. ''Sometimes I am asked why I was so pessimistic in 'Foreign Land' and why I open the possibility of optimism with 'Central Station,' '' Mr. Salles said. ''But the films portray different moments of Brazilian reality.''

He paused. ''When you see films today, it seems that most of the characters endure a situation they cannot control,'' he said. ''Here I wanted to show that tough as life may be, it can be possible to transcend this initial adversity.''

That hopeful message may explain the widespread appeal of ''Central Station.'' The film has been a big success in Brazil, where it has been seen by more than a million viewers, but it also had positive audience response at the Sundance, Toronto and Berlin film festivals. ''During the screenings we held in Toronto, I saw tears rolling down people's faces,'' said Ramiro Puerta, the programmer for Latin American and Spanish films in Toronto.

As the film opens around the world, Mr. Salles's own life these days resembles a road movie. But even in the wake of ''Central Station's'' success, he has no plans to relocate from Rio -- where he lives in a forested area outside the city with his six large dogs -- or to change his thematic pursuits.

With Daniela Thomas, a co-director of ''Foreign Land,'' Mr. Salles has written and directed a short feature called ''Midnight,'' and he will work again with Arthur Cohn on two films still being written.

Embarking on these projects, Mr. Salles seems to want to explore further the need for connection -- whether between individuals or between peoples -- that ''Central Station'' embraces. '' 'Central Station' is much more about brotherhood than it is about a specific country,'' he said. ''Even as an artist, you need to know that what you do is part of a larger whole. You need to be part of a dialogue.'' He smiled. ''In Brazil, we have this expression: 'One bird alone does not announce the spring.' ''