善良无需考证

巴西著名导演沃尔特·塞勒斯正在筹备自己的新电影,一天,正为此一筹莫展的沃尔特到城市西郊办事,在火车站前的广场上遇到了一个十多岁的擦鞋小男孩。小男孩问道:「先生,您需要擦鞋吗?」沃尔特低头看了看自己脚上刚刚擦过不久的皮鞋,摇摇头拒绝了。

就在沃尔特转身走出十几步之际,忽然见到那个小男孩红著脸追上来,眼中满是祈求:「先生,我整整一天都没吃东西了,您能借给我几个钱吗?我从明天开始就多多努力擦鞋,保证一周后把钱还给您!」

沃尔特看着面前这个衣衫褴褛、面黄肌瘦的小男孩,不由的动了恻隐之心,就掏出几枚硬币递到小男孩手里。小男孩感激的道了一声「谢谢」后,一溜烟就跑得没影了。沃尔特摇了摇头,因为这样的街头小骗子他已经见得太多了。

半个月后,忙着筹备新电影的沃尔特早已将借钱给小男孩的事忘得一干二净了。不料,就在他又一次经过西郊火车站时,突然看到一个瘦小的身影离的老远就向他招手喊道:「先生,请等一等!」等到对方满头大汗的跑过来把几枚硬币交给他时,沃尔特才认出这是上次向他借钱的那个擦鞋小男孩。小男孩气喘吁吁的说:「先生,我在这里等您很久了,今天总算把钱还给您了!」沃尔特握著自己手里被汗水濡湿的硬币,心头陡然升起一股暖流。

沃尔特不由地仔细端详起面前的小男孩,突然,他发现这个小男孩其实很符合自己脑海中构想的主人公形象。于是,沃尔特把几枚硬币塞到小男孩衣兜里:「这点零钱是我诚心诚意给你的,就不用还了。」沃尔特对他神秘的一笑,又说道,「明天你到市中心的影业公司导演办公室来找我,我会给你一个大大的惊喜。」

第二天一大早,门卫就告诉沃尔特,说外面来了一大群孩子。他诧异的出去一看,就见那个小男孩兴奋的跑过来,一脸天真的说:「先生,这些孩子都是同我一样没有父母的流浪儿,听说你有惊喜给我,我就把他们都带来了,因为,我知道他们也渴望有惊喜!」

沃尔特真没想到这样一个穷困流浪的孩子竟会有一颗如此善良的心!既然人都带来了,沃尔特就让工作人员对这些孩子进行了观察和筛选,最后,工作人员在这些孩子中,找出了几个比小男孩更机灵,更适合出演剧本中的小主人公的人选。

但最终,沃尔特还是选择只把小男孩留下来。他在录用合同的免试原因一栏中只写了这样几个字:你的善良,无需考核!

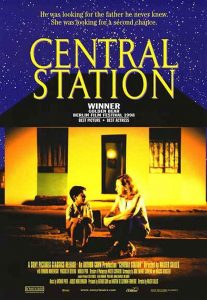

因为他觉得:在自己面临困境的时候,却依然能把本属于自己一个人的希望,无私的分享给别人的人,最值得拥有人生的惊喜!而这个小男孩就是后来巴西家喻户晓的明星文尼西斯·狄·奥利维拉。 在沃尔特的执导下,文尼西斯在剧中成功地扮演了小男孩主人公的角色,而电影《中央车站》也大获好评,并获得了1999年的奥斯卡金像奖。

若干年后,已成为一家影视文化公司董事长的文尼西斯写了一本自传,叫《我的演艺生涯》。

在书的扉页上面,是沃尔特的亲笔题字:你的善良,无需考核。下面还有一行小字,则是他对文尼西斯的评价:「是善良,曾经让他把机遇让给别的孩子;同样也是善良,让人生的机遇不曾错过他!」。

「欣赏一个人,始于颜值,敬于才华,合于性格,久于善良,终于人 品。

人生就是这样,和漂亮的人在一起,会越来越美;和阳光的人在一起,心里就不会晦暗;和快乐的人在一起,嘴角就常带微笑;和聪明的人在一起,做事就机敏;和大方的人在一起, 处事就不小气;和睿智的人在一起,遇事就不迷茫。

借人之智,修善自己;学最好的别人,做最好的自己!」

(English story from Washington Post, different from Chinese one, good for reading )

ONE morning in late 1996, the Brazilian director Walter Salles was waiting for a flight in Rio de Janeiro when he was approached by a 9-year-old shoeshine boy. At the time, Mr. Salles was preparing to shoot his third feature film, ''Central Station,'' the tale of an older woman and a boy who meet at Rio's train station and then strike out on a journey into the hinterlands to find the boy's father.

Fernanda Montenegro, Brazil's doyenne of stage and film, had agreed to play the woman, Dora, but Mr. Salles had still not found anyone to play Josue, the child. ''In one full year we had tested 1,500 boys,'' he said. ''I was getting desperate.''

The shoeshine boy, Vinicius de Oliveira, had other concerns, however. ''It was raining that day, and I wasn't making any money,'' he recalled, speaking through an interpreter at the Toronto Film Festival. ''I couldn't shine Walter's shoes because he was wearing sneakers, but I asked if he could lend me some money so I could eat and I would pay him back. He told me, 'I'll give you the money to buy a sandwich, but you also have to do a screen test for me.' ''

When Vinicius finally showed up for the test, he brought his friends with him, ''the entire fraternity of shoeshine boys from the airport,'' Mr. Salles said, laughing. He chose Vinicius for the role because, he said, ''I was looking for a boy who knew what the battle for survival was, but who had not lost his innocence in doing so.

''I cannot even say that I found Vinicius. It's more honest to say that he found me.''

The story of how ''Central Station'' was made, over a vast territory, with a small budget and crew and many novice collaborators, embodies the theme of the film itself: the triumph of steadfastness over adversity. Both a portrait of present day Brazil and a two-person drama, ''Central Station,'' which opened on Friday, manages to be intimate and epic, local and universal.

''One day I woke up with this idea of a film about a quest,'' said Mr. Salles, 42. ''It was the search for a father that a kid had never met, the search of an old woman for the feelings that she had lost and the search somehow for a certain country that was not the country I was living in anymore.''

Mr. Salles's work is informed by the search for identity, both on a personal and national level, a concern stemming largely from his own background. Born in Brazil to a banking family, he spent part of his childhood in France and the United States where his father was a diplomat. When he returned to Brazil, he eventually decided to become a documentary filmmaker.

This combination of an outsider's perspective and an insider's understanding has shaped Mr. Salles's work. ''I think the fact that I have been raised in several different countries has given me both a sense of continuous exile and a desire to understand my own culture,'' he said recently in New York, speaking in fluent English.

The dark-haired Mr. Salles, who has kind eyes and a ready laugh, is both warm and disarmingly modest. ''When you come from a privileged part of Brazilian society, as I do, you have to opt either to be part of that culture of indifference or to understand what the country really is,'' he said.

His movie comes at a time when Brazilian cinema is once again flourishing. After a period of forced inactivity in the early 1990's, when the Government of President Fernando Collor de Mello froze individual bank accounts and shut down the state film agency, film production has risen to approximately 40 films a year.

But the reality of everyday life that ''Central Station'' depicts is harsh. In the film, Dora is a bitter woman who makes her living in Rio's Central Station, writing letters for illiterate people. She takes their money but discards the letters. One day she writes a letter for a mother and her little boy (Vinicius de Oliveira). When the mother is killed in an accident outside the station, Dora tries to sell the boy for adoption. Realizing that she has instead sold him to a sinister organization in which he may come to harm, she rescues the boy and the two set out on a bus trip to find his father.

For Mr. Salles, Dora is the epitome of modern Brazil, with its ''culture of cynicism.'' But as Dora grudgingly develops a bond with the boy ''she begins to understand that the boy's route and the boy's ordeal are comparable to her own,'' he said.

The growing friendship between these two -- more comradely than mother-son -- is, for Mr. Salles, a symbol of a Brazil where solidarity and compassion may be buried but are still present. His film is not utopian, but it celebrates the diversity both of the land and of what Mr. Salles calls the ''human geography'' that Dora and Josue encounter on their journey.

When the screenplay of ''Central Station,'' based on an idea of Mr. Salles's and written by Joao Emanuel Carneiro and Marcos Bernstein, won a prize sponsored by the Sundance Institute and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation in early 1996, it attracted the attention of Arthur Cohn, the Swiss independent producer who has won five Academy Awards (one for Vittorio De Sica's ''Garden of the Finzi-Continis'').

LIKE De Sica, Walter's approach is humanistic,'' said Mr. Cohn. ''De Sica taught me that there were four main points to making significant films. One was to cast actors who are right for the part, not just those with big names. Two was to shoot the film on authentic locations. Three was that sex, violence or special effects are not necessary unless they're intrinsic to the story.'' He smiled. ''Four was not to listen to everybody's advice, but to follow your intuition.''

With Mr. Cohn as producer, and with his principal cast finally in place Mr. Salles started the collaborative rehearsal process he had favored with his second film, ''Foreign Land'' (1995). ''It's a work almost like that of theater,'' said Ms. Montenegro, 69, in New York. ''For two months we sat around a table, reading and discussing the script.''

The long preparation allowed Mr. Salles to move quickly and to improvise once filming began in November 1996. During the filming of Ms. Montenegro's scenes in the railroad station, several passersby took her to be an actual letter-writer and asked her to write letters for them, scenes that made it into the movie. In following the journey of Dora and Josue, Mr. Salles had to move his team from Rio to remote regions of northeast Brazil, to the states of Bahia and Pernambuco. ''The transport from one place to another sometimes took three days on dirt roads,'' said Mr. Salles. ''It was like being in a circus for several weeks.''

Nor were conditions easy, due to the extreme heat and the poverty of the villages where Mr. Salles was filming. Yet the welcome that his crew received allowed the unforeseen to occur, as in a scene where Dora and Josue come upon a religious pilgrimage in full swing. Mr. Salles had the actual pilgrims recreate this candlelight vigil.

Mr. Salles is a largely self-taught filmmaker. After studying history and economics in college in Brazil, he attended only one year of film school, at the University of Southern California, before returning to Rio in 1981 to make documentaries.

His move toward feature films was gradual. In 1989, he directed ''Exposure,'' starring Peter Coyote and based on the Brazilian writer Rubem Fonseca's novel ''High Art.'' ''Foreign Land,'' about two young Brazilians bereft in Lisbon, delved into the themes of physical and spiritual voyage and of loss. ''Sometimes I am asked why I was so pessimistic in 'Foreign Land' and why I open the possibility of optimism with 'Central Station,' '' Mr. Salles said. ''But the films portray different moments of Brazilian reality.''

He paused. ''When you see films today, it seems that most of the characters endure a situation they cannot control,'' he said. ''Here I wanted to show that tough as life may be, it can be possible to transcend this initial adversity.''

That hopeful message may explain the widespread appeal of ''Central Station.'' The film has been a big success in Brazil, where it has been seen by more than a million viewers, but it also had positive audience response at the Sundance, Toronto and Berlin film festivals. ''During the screenings we held in Toronto, I saw tears rolling down people's faces,'' said Ramiro Puerta, the programmer for Latin American and Spanish films in Toronto.

As the film opens around the world, Mr. Salles's own life these days resembles a road movie. But even in the wake of ''Central Station's'' success, he has no plans to relocate from Rio -- where he lives in a forested area outside the city with his six large dogs -- or to change his thematic pursuits.

With Daniela Thomas, a co-director of ''Foreign Land,'' Mr. Salles has written and directed a short feature called ''Midnight,'' and he will work again with Arthur Cohn on two films still being written.

Embarking on these projects, Mr. Salles seems to want to explore further the need for connection -- whether between individuals or between peoples -- that ''Central Station'' embraces. '' 'Central Station' is much more about brotherhood than it is about a specific country,'' he said. ''Even as an artist, you need to know that what you do is part of a larger whole. You need to be part of a dialogue.'' He smiled. ''In Brazil, we have this expression: 'One bird alone does not announce the spring.' ''